Syncytium

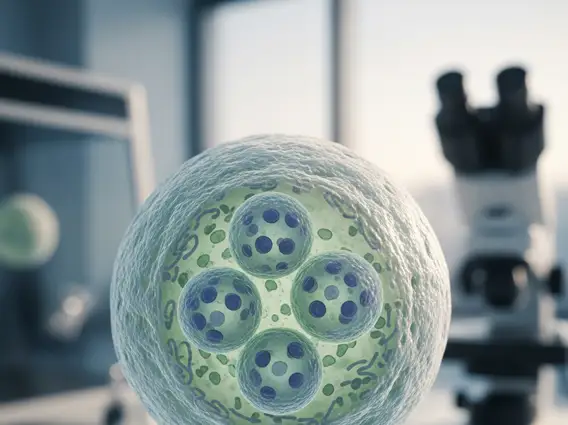

A syncytium is a fascinating biological structure characterized by a single, continuous cytoplasm containing multiple nuclei. This unique cellular arrangement plays crucial roles in various physiological processes across different organisms.

Key Takeaways

- A syncytium is a multinucleated cell formed either by the fusion of several individual cells or by multiple nuclear divisions without subsequent cell division.

- This structure allows for efficient communication and coordinated function across a large cytoplasmic volume.

- Key examples include skeletal muscle fibers, the placental syncytiotrophoblast, and osteoclasts, each performing vital biological roles.

- Its formation is a regulated process, essential for development, tissue repair, and specialized physiological functions.

Understanding What is Syncytium

A Syncytium refers to a multinucleated cell that functions as a single unit. This distinctive cellular architecture is fundamental to understanding various biological systems. The syncytium definition biology describes it as a mass of cytoplasm that is not subdivided into individual cells, yet contains numerous nuclei. This differs from a coenocyte, which also has multiple nuclei but typically arises from repeated nuclear divisions within a single cell without cytokinesis (cell division), whereas a syncytium often forms through the fusion of multiple originally separate cells.

The presence of multiple nuclei within a shared cytoplasm allows for efficient distribution of resources, rapid communication, and coordinated gene expression across a larger functional unit. This structural adaptation is critical for tissues requiring high metabolic activity, rapid force generation, or extensive transport functions, enabling them to perform specialized tasks more effectively than individual mononucleated cells could.

How Syncytium Forms in Cells

The formation of a syncytium is a precisely regulated process that can occur through two primary mechanisms. One common method involves the fusion of multiple individual mononucleated cells. During this process, the plasma membranes of adjacent cells merge, leading to the coalescence of their cytoplasms and the integration of their nuclei into a single, larger cellular entity. This cell fusion often involves specific fusogenic proteins on the cell surfaces that mediate the recognition and merging of membranes.

Alternatively, a syncytium can form through repeated nuclear divisions within a single cell without subsequent cytokinesis. In this scenario, the cell grows and its nucleus divides multiple times, but the cytoplasm does not partition to form separate daughter cells. Instead, all the newly formed nuclei remain within the original cell’s boundaries. Both mechanisms result in a functional unit with shared cytoplasmic resources, allowing for coordinated cellular activities crucial for development and physiological function.

Syncytium Examples and Biological Functions

The biological significance of syncytia is evident in their diverse roles across various tissues and organisms. Understanding syncytium examples and function highlights their importance in development, physiology, and even pathology. Here are some prominent examples:

- Skeletal Muscle Fibers: These are perhaps the most well-known examples of syncytia. Formed by the fusion of numerous myoblasts (muscle precursor cells) during development, skeletal muscle fibers are long, cylindrical cells containing hundreds of nuclei. This multinucleated structure is crucial for their primary function of generating strong, coordinated contractions, as it allows for efficient protein synthesis and repair throughout the extensive cytoplasm.

- Placental Syncytiotrophoblast: This outer layer of the placenta is a massive syncytium formed by the continuous fusion of underlying cytotrophoblast cells. It plays a vital role in mediating nutrient and gas exchange between the mother and fetus, producing essential hormones (like human chorionic gonadotropin), and forming a protective barrier against maternal immune responses.

- Osteoclasts: These large, multinucleated cells are responsible for bone resorption. They form by the fusion of monocyte-macrophage lineage precursor cells. Their syncytial nature enables them to effectively break down bone tissue, a process critical for bone remodeling and calcium homeostasis.

- Cardiac Muscle (Functional Syncytium): While not a true anatomical syncytium (cardiac muscle cells are individual, mononucleated cells), they function as a “functional syncytium.” This is due to the presence of gap junctions, which allow rapid electrical communication and ion flow between adjacent cells, enabling the heart muscle to contract in a coordinated, wave-like fashion.

These examples illustrate how the syncytial arrangement provides specific advantages, such as enhanced metabolic capacity, efficient transport, and coordinated mechanical force generation, enabling tissues to perform highly specialized and critical biological functions.