Key Takeaways

- Ocular melanoma is a rare cancer originating in the eye’s pigment-producing cells, most commonly affecting the uvea.

- Early ocular melanoma symptoms are often subtle or absent, making regular dilated eye exams crucial for early detection.

- Diagnosis relies on specialized eye exams, imaging, and sometimes biopsy to determine the types of ocular melanoma and its extent.

- Ocular melanoma treatment options vary based on tumor size and location, including radiation, surgery, and targeted therapies.

- The ocular melanoma prognosis is influenced by several factors, including tumor size, location, and genetic markers, with early detection significantly improving outcomes.

What Is Ocular Melanoma?

Ocular melanoma is a malignant tumor that forms in the melanocytes, the cells responsible for producing pigment (melanin), within the eye. While it shares similarities with skin melanoma, it is a distinct disease. It is the most common primary intraocular malignancy in adults, though it remains relatively rare compared to other cancers. According to the American Academy of Ophthalmology, the incidence of uveal melanoma, the most common form, is approximately 5-6 cases per million people per year in the United States.

Understanding Different Types

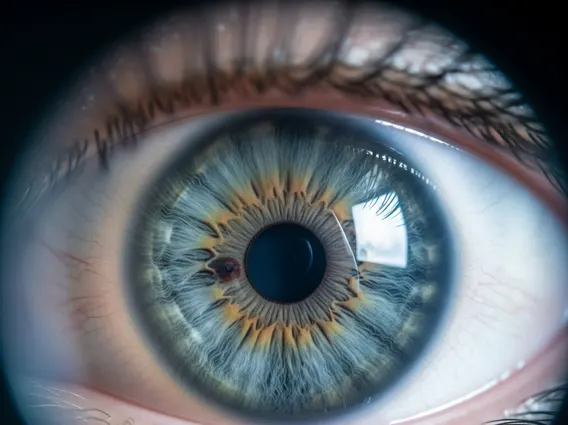

The types of ocular melanoma are primarily classified by their location within the eye:

- Uveal Melanoma: This is the most prevalent form, accounting for about 90% of all ocular melanomas. The uvea is the middle layer of the eye wall, comprising three parts:

- Choroid: The most common site for uveal melanoma, located at the back of the eye, supplying blood and nutrients to the retina.

- Ciliary Body: Located behind the iris, it produces aqueous humor and helps change the shape of the lens.

- Iris: The colored part of the eye, iris melanomas are usually smaller and have a better prognosis.

- Conjunctival Melanoma: This type develops on the conjunctiva, the clear membrane covering the white part of the eye and the inside of the eyelids. It is much rarer than uveal melanoma.

- Eyelid Melanoma: While often considered a type of skin melanoma, it can affect the eyelid skin and surrounding structures.

Understanding what is ocular melanoma and its specific type is crucial for determining the most effective treatment strategy.

Symptoms and Risk Factors

Recognizing the signs and understanding potential risk factors are vital for early detection and intervention in cases of ocular melanoma.

Key Signs to Watch For

In its early stages, ocular melanoma symptoms are often subtle or entirely absent, as the tumor may not affect vision or cause discomfort. This is why regular comprehensive eye exams are so important. When symptoms do appear, they can include:

- Blurred vision or a sudden decrease in vision, particularly in one eye.

- Seeing flashes of light or an increase in “floaters” (small specks or threads that drift across the field of vision).

- A dark spot on the iris that is growing or changing in appearance.

- A change in the shape of the pupil.

- A sensation of pressure or pain in the eye (this is rare and usually indicates a larger tumor).

- Changes in the position of the eyeball within the socket.

Any persistent changes in vision or eye appearance warrant immediate consultation with an ophthalmologist.

Potential Causes and Risk Factors

The exact causes of ocular melanoma are not fully understood, but research points to genetic mutations and several risk factors. Unlike skin melanoma, direct sun exposure is not as clearly linked, although some studies suggest a possible association. Key risk factors include:

- Light Eye Color: Individuals with blue, green, or grey eyes have a higher risk.

- Fair Skin: People with fair skin, who tend to sunburn easily, are at increased risk.

- Age: The risk of developing ocular melanoma increases with age, most commonly diagnosed in people over 50.

- Certain Inherited Conditions: Conditions like dysplastic nevus syndrome or BAP1 tumor predisposition syndrome can increase susceptibility.

- Presence of Ocular Melanocytosis or Nevus of Ota: These are benign conditions involving increased pigment in or around the eye, which can rarely transform into melanoma.

- Genetic Mutations: Specific mutations, particularly in the GNAQ and GNA11 genes, are frequently found in uveal melanoma cells.

It is important to note that having one or more risk factors does not guarantee the development of ocular melanoma, but it does highlight the importance of regular eye screenings.

Diagnosing Ocular Melanoma

The accurate diagnosis of ocular melanoma is critical for effective treatment planning. Due to the often asymptomatic nature of early tumors, diagnosis typically occurs during routine dilated eye examinations or when a patient presents with new visual symptoms. An ophthalmologist, particularly one specializing in ocular oncology, will perform a thorough evaluation.

Diagnostic procedures commonly include:

- Dilated Eye Exam: The pupil is widened with drops to allow the doctor to view the back of the eye with an ophthalmoscope. This can reveal abnormal pigmented lesions.

- Ocular Ultrasound: This non-invasive test uses sound waves to create detailed images of the eye’s internal structures, helping to determine the size, shape, and location of the tumor.

- Fluorescein Angiography: A dye is injected into a vein, and photographs are taken as it circulates through the eye’s blood vessels, highlighting abnormal vascular patterns associated with tumors.

- Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT): This imaging technique provides high-resolution cross-sectional images of the retina and choroid, useful for assessing tumor characteristics.

- Fundus Photography: Captures detailed images of the retina, optic disc, and choroid, allowing for documentation and monitoring of suspicious lesions over time.

- Biopsy: While less common for uveal melanoma due to potential risks, a fine-needle aspiration biopsy may be performed in some cases to confirm the diagnosis and obtain genetic information about the tumor, which can guide prognosis and treatment.

Once diagnosed, the tumor will be staged to determine if it has spread beyond the eye, which influences the treatment approach.

Treatment Options and Outlook

Managing ocular melanoma requires a multidisciplinary approach, with treatment plans tailored to the individual patient based on the tumor’s size, location, and whether it has spread.

Overview of Therapies

A range of ocular melanoma treatment options are available, aiming to eradicate the tumor while preserving as much vision as possible. These include:

- Radiation Therapy:

- Brachytherapy (Plaque Radiotherapy): This is the most common treatment for small to medium-sized tumors. A small radioactive disc (plaque) is surgically attached to the outside of the eye over the tumor for several days, delivering localized radiation.

- External Beam Proton Therapy: High-energy proton beams are precisely directed at the tumor from outside the eye, sparing surrounding healthy tissue. It is often used for larger tumors or those in difficult-to-reach locations.

- Surgery:

- Enucleation: Surgical removal of the entire eye is typically reserved for very large tumors, those causing significant pain, or when vision is already lost. An ocular prosthesis is then fitted.

- Iridectomy/Iridocyclectomy: For very small tumors affecting the iris or ciliary body, a portion of the iris or ciliary body may be surgically removed.

- Laser Therapy (Transpupillary Thermotherapy – TTT): This involves using a focused infrared laser to heat and destroy small tumors, often used in conjunction with radiation therapy.

- Targeted Therapy and Immunotherapy: For metastatic ocular melanoma (cancer that has spread beyond the eye), systemic treatments like targeted therapy (e.g., tebentafusp) and immunotherapy are increasingly used. These therapies aim to harness the body’s immune system or target specific molecular pathways to fight cancer cells.

The choice of therapy is a complex decision made in consultation with an ocular oncologist, considering the potential benefits and risks of each approach.

Factors Affecting Prognosis

The ocular melanoma prognosis varies significantly among individuals and depends on several key factors. Early detection and treatment generally lead to better outcomes. Important prognostic indicators include:

- Tumor Size and Location: Smaller tumors and those located in the iris tend to have a better prognosis than larger tumors or those in the ciliary body, which are more prone to metastasis.

- Cell Type: The microscopic appearance of the tumor cells (histopathology) plays a role. Spindle cell melanomas generally have a better prognosis than epithelioid cell melanomas.

- Genetic Markers: Specific genetic mutations within the tumor, particularly mutations in the BAP1 gene, are strongly associated with a higher risk of metastasis and a poorer prognosis. Genetic testing of the tumor can provide valuable prognostic information.

- Presence of Metastasis: If the cancer has spread to other parts of the body, particularly the liver, the prognosis is significantly worse. The 5-year survival rate for localized uveal melanoma is approximately 82%, but drops to around 15% if the cancer has spread to distant sites, according to the American Cancer Society.

- Age: Younger patients often have a slightly better prognosis than older patients.

Regular follow-up examinations are crucial after treatment to monitor for recurrence or metastasis, which can occur many years after the initial diagnosis.

Ocular melanoma is considered a rare cancer. Uveal melanoma, its most common form, affects approximately 5 to 6 people per million in the United States annually. This makes it significantly less common than skin melanoma. Its rarity often means that general practitioners or even general ophthalmologists may encounter it infrequently, underscoring the importance of referral to specialized ocular oncologists for accurate diagnosis and treatment. Despite its rarity, it is the most common primary eye cancer in adults.

Currently, there are no definitive prevention strategies for ocular melanoma, as its exact causes are not fully understood. While some studies suggest a possible link to UV exposure, it’s not as strong as with skin melanoma. However, protecting your eyes from excessive UV radiation by wearing sunglasses that block 99-100% of UVA and UVB rays is generally recommended for overall eye health. Regular comprehensive dilated eye exams, especially for individuals with risk factors like light eye color or certain inherited conditions, are the best way to ensure early detection.

The long-term effects of ocular melanoma treatment vary depending on the specific therapy used and the tumor’s characteristics. Radiation therapy can lead to vision loss in the treated eye, dry eye, or radiation retinopathy over time. Surgical removal of the eye (enucleation) results in permanent vision loss in that eye, though a prosthetic eye can provide a natural appearance. Patients often require lifelong monitoring for potential recurrence or metastasis, particularly to the liver. Regular follow-up with an ocular oncologist is essential to manage any long-term complications and ensure overall health.