Perfusion

Perfusion is a fundamental physiological process vital for the health and function of every cell, tissue, and organ in the human body. Understanding this critical mechanism is essential for comprehending overall physiological well-being and various medical conditions.

Key Takeaways

- Perfusion is the delivery of blood to a capillary bed in tissues.

- It ensures cells receive oxygen and nutrients while efficiently removing waste products.

- Effective perfusion is crucial for optimal organ function and overall health.

- Impaired perfusion can lead to cellular damage, tissue dysfunction, and organ failure.

- Medical professionals closely monitor perfusion to assess a patient’s circulatory status and organ viability.

What is Perfusion: Medical Definition

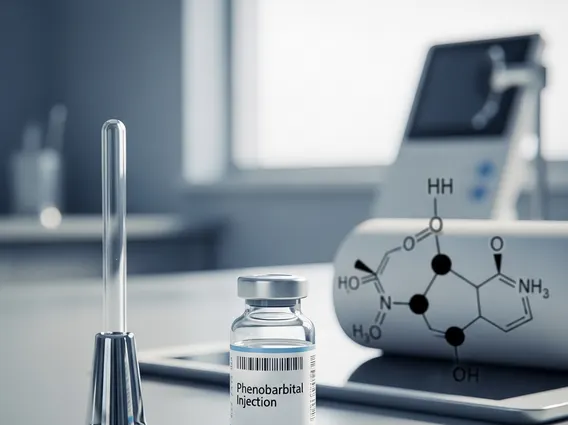

Perfusion refers to the vital physiological process by which the body delivers blood to a capillary bed within its biological tissue. This continuous and regulated supply of blood is absolutely essential for sustaining cellular life, as it provides oxygen, vital nutrients, and hormones to cells, while simultaneously efficiently removing metabolic waste products such as carbon dioxide and lactic acid. The overall efficiency of perfusion directly impacts cellular metabolism, tissue viability, and the optimal function of entire organs.

From a perfusion definition medical perspective, it is precisely measured as the rate at which blood flows through the intricate microvasculature of a specific tissue. This rate is dynamically influenced by a complex interplay of factors including systemic blood pressure, localized vascular resistance, and the specific metabolic demands of the tissue itself. Adequate perfusion is a critical indicator of healthy tissue, signifying that cells are receiving all the necessary resources to perform their specialized functions optimally and maintain homeostasis.

How Perfusion Works: The Physiological Process

The physiological process of how perfusion works involves a highly coordinated and complex interplay of the entire cardiovascular system, which includes the heart, an extensive network of blood vessels, and the blood itself. The heart functions as the central pump, generating the necessary pressure to propel blood throughout the entire circulatory system. Arteries are responsible for carrying oxygenated blood away from the heart, progressively branching into smaller arterioles, and ultimately into the microscopic capillaries where the crucial exchange of substances between blood and tissue occurs.

At the capillary level, oxygen and essential nutrients readily diffuse from the blood into the surrounding tissue cells, driven by concentration gradients. Concurrently, carbon dioxide and other metabolic waste products move from the cells back into the blood, facilitated by similar gradients, to be transported away for excretion. This intricate exchange mechanism is also influenced by hydrostatic pressure. Following this exchange, the blood collects in venules, which then merge to form larger veins, returning deoxygenated blood to the heart and lungs for reoxygenation. The body possesses sophisticated regulatory mechanisms to constantly adjust blood flow to different organs based on their immediate metabolic needs, ensuring that vital organs receive preferential perfusion during periods of increased demand or physiological stress.

- Cardiac Output: This represents the volume of blood pumped by the heart per minute, serving as a primary determinant of systemic perfusion throughout the body.

- Vascular Tone: Refers to the degree of constriction or relaxation of blood vessels, a critical factor that regulates both blood pressure and the precise distribution of blood flow to various tissues.

- Microcirculation: This term describes the intricate network of arterioles, capillaries, and venules where the vital nutrient and waste exchange processes take place at the cellular level.

- Autoregulation: These are local, intrinsic mechanisms within individual tissues that automatically adjust blood flow to maintain a relatively constant perfusion, even in the face of fluctuations in systemic blood pressure.

The Importance of Perfusion for Organ Health

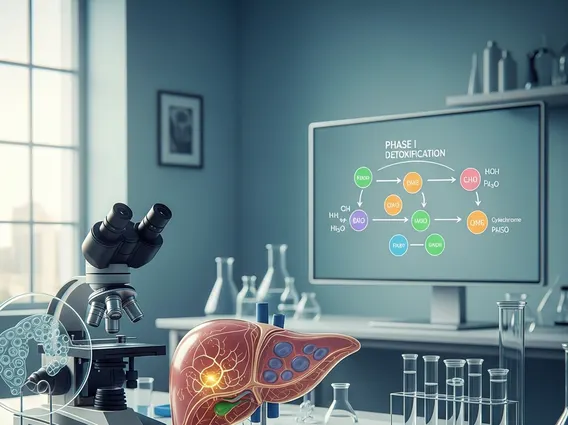

The profound importance of perfusion cannot be overstated when considering the health and optimal functioning of individual organs and the overall physiological integrity of the body. Every single organ, from the highly active brain and the tirelessly pumping heart to the filtering kidneys and the metabolically active liver, relies absolutely on a consistent and adequate supply of oxygenated blood to perform its specialized tasks effectively. Without sufficient perfusion, cells rapidly begin to suffer from hypoxia (a critical lack of oxygen) and severe nutrient deprivation, leading to impaired function and, if prolonged, potentially irreversible tissue damage or necrosis.

For example, the human brain demands a constant and robust flow of blood to support its exceptionally high metabolic rate; even brief interruptions in this supply can quickly cause significant neurological deficits. Similarly, the kidneys are entirely dependent on robust perfusion to efficiently filter waste products from the blood, regulate electrolyte balance, and maintain overall fluid homeostasis. Chronic medical conditions that compromise perfusion, such as advanced atherosclerosis, congestive heart failure, or severe shock, can lead to widespread organ dysfunction and contribute significantly to serious, life-threatening health complications. Therefore, maintaining optimal perfusion is a critical and continuous goal in medical care, frequently monitored closely in critically ill patients to prevent the onset or progression of organ failure and ensure patient survival.