Key Takeaways

- Acute Myeloid Leukemia is a fast-growing cancer originating in the bone marrow, characterized by the overproduction of abnormal white blood cells.

- Common symptoms of acute myeloid leukemia include fatigue, easy bruising, fever, and frequent infections, often appearing suddenly.

- While the exact causes of acute myeloid leukemia are often unknown, genetic mutations and environmental factors like exposure to certain chemicals or prior chemotherapy are recognized risk factors.

- Diagnosing acute myeloid leukemia involves blood tests, bone marrow biopsy, and genetic analysis, which are critical for determining the specific type and guiding treatment.

- Treatment options for AML typically include intensive chemotherapy, targeted therapies, and stem cell transplantation, with acute myeloid leukemia prognosis varying significantly based on age, genetics, and response to therapy.

About Acute Myeloid Leukemia

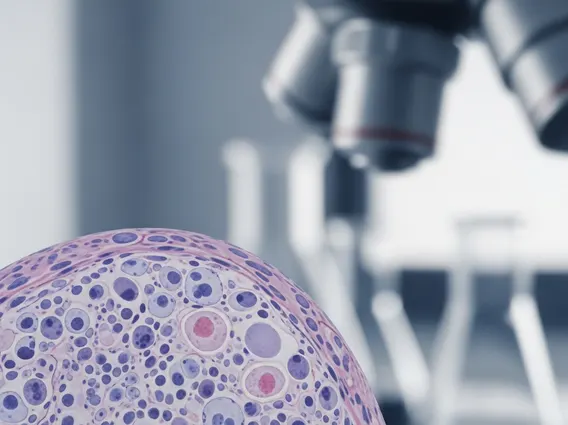

Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) is a type of cancer that starts in the bone marrow, the soft, spongy tissue inside bones where blood cells are made. It affects the myeloid stem cells, which normally mature into various types of blood cells, including red blood cells, platelets, and most types of white blood cells. In AML, these myeloid stem cells fail to mature properly and instead develop into abnormal, immature white blood cells called myeloblasts or leukemia cells. These abnormal cells multiply rapidly, accumulating in the bone marrow and blood, thereby interfering with the production of normal, healthy blood cells.

How AML Develops

The development of AML begins when a single myeloid stem cell in the bone marrow acquires genetic mutations. These mutations disrupt the normal processes of cell growth, division, and maturation. Instead of developing into functional blood cells, the mutated stem cell produces a large number of immature and non-functional myeloblasts. These leukemia cells then crowd out the healthy cells in the bone marrow, leading to a deficiency of red blood cells (anemia), platelets (thrombocytopenia), and functional white blood cells (leukopenia or neutropenia), which are essential for oxygen transport, clotting, and fighting infections, respectively.

Types of AML

AML is not a single disease but rather a group of related cancers, classified based on the specific type of myeloid cell involved and, more importantly, on the genetic and molecular changes within the leukemia cells. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification system is widely used, categorizing AML into several subtypes. These classifications are crucial because they influence the choice of treatment options for AML and provide insights into the acute myeloid leukemia prognosis. For instance, some subtypes are associated with specific chromosomal abnormalities or gene mutations that respond better to certain targeted therapies.

Recognizing the Symptoms of AML

The symptoms of acute myeloid leukemia often appear suddenly and can worsen quickly due to the rapid proliferation of leukemia cells and the resulting deficiency of normal blood cells. Because these symptoms can be vague and mimic other common illnesses, early recognition can be challenging but is vital for prompt diagnosis and treatment.

Early Warning Signs

Many early warning signs of AML are related to the reduced production of healthy blood cells. Patients may experience persistent fatigue and weakness, resulting from anemia (low red blood cell count). Easy bruising or bleeding, such as nosebleeds or gum bleeding, can occur due to thrombocytopenia (low platelet count). Frequent infections and fevers are common because the body lacks sufficient functional white blood cells to fight off pathogens. Other general symptoms might include shortness of breath, pale skin, and dizziness.

Advanced Symptoms

As the disease progresses and leukemia cells accumulate, more severe and specific symptoms can emerge. These may include unexplained weight loss and loss of appetite. Some patients might develop swollen lymph nodes, an enlarged spleen, or an enlarged liver, as leukemia cells can infiltrate these organs. Bone or joint pain can also occur if the bone marrow is heavily infiltrated with leukemia cells. In rare cases, leukemia cells can spread to the central nervous system, causing headaches, seizures, or vision changes, or to the gums, leading to swelling and bleeding.

Causes and Risk Factors for Acute Myeloid Leukemia

The precise causes of acute myeloid leukemia are often unknown, and in most cases, it develops without any clear identifiable reason. However, research has identified several factors that can increase an individual’s risk of developing AML. These factors are generally categorized into genetic predispositions and environmental exposures.

Genetic Mutations

AML is primarily caused by acquired (not inherited) genetic mutations in the DNA of bone marrow stem cells. These mutations lead to uncontrolled growth and impaired maturation of myeloid cells. While these mutations are not typically passed down through families, certain inherited genetic syndromes, such as Down syndrome, Fanconi anemia, or Bloom syndrome, can increase the risk of developing AML. Specific gene mutations, like those in FLT3, NPM1, or CEBPA, are commonly found in AML patients and are crucial for classifying the disease and guiding targeted therapies.

Environmental Influences

Exposure to certain environmental factors and prior medical treatments can also elevate the risk of AML. These include:

- Exposure to certain chemicals: Prolonged exposure to chemicals like benzene, found in gasoline, tobacco smoke, and some industrial products, is a known risk factor.

- Previous cancer treatment: Patients who have received chemotherapy or radiation therapy for other cancers have an increased risk of developing secondary AML, often years after their initial treatment.

- Smoking: Tobacco smoke contains carcinogens, including benzene, which can contribute to the development of AML.

- High-dose radiation exposure: Exposure to very high levels of radiation, such as from a nuclear accident, significantly increases AML risk.

- Other blood disorders: Individuals with certain pre-existing blood disorders, such as myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) or myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN), have a higher chance of their condition transforming into AML.

It is important to note that most people with these risk factors do not develop AML, and many people with AML have no known risk factors.

Diagnosing Acute Myeloid Leukemia

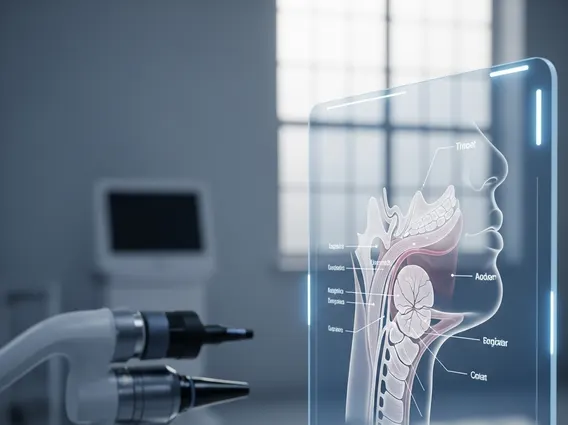

Accurate and timely diagnosing acute myeloid leukemia is critical for initiating appropriate treatment and improving patient outcomes. The diagnostic process typically involves a combination of blood tests, bone marrow examination, and specialized genetic analyses.

Diagnostic Tests

The initial step in diagnosing AML usually involves a complete blood count (CBC), which can reveal abnormal levels of white blood cells (often very high, but sometimes low), a low red blood cell count (anemia), and a low platelet count (thrombocytopenia). If these results are suspicious, further tests are performed:

| Test | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Bone Marrow Aspiration and Biopsy | A definitive diagnostic procedure where samples of liquid marrow and solid bone are taken, usually from the hip bone. These samples are examined under a microscope to identify the presence and percentage of myeloblasts. A diagnosis of AML typically requires at least 20% myeloblasts in the bone marrow or blood. |

| Cytogenetics | Analyzes the chromosomes in the leukemia cells to detect specific abnormalities (e.g., translocations, deletions). These findings are crucial for classifying the AML subtype and predicting treatment response. |

| Molecular Testing | Looks for specific gene mutations (e.g., FLT3, NPM1, CEBPA) that are not visible through cytogenetics. These mutations can influence prognosis and guide the use of targeted therapies. |

| Flow Cytometry | Identifies specific proteins on the surface of leukemia cells, helping to confirm the myeloid lineage and differentiate AML from other types of leukemia. |

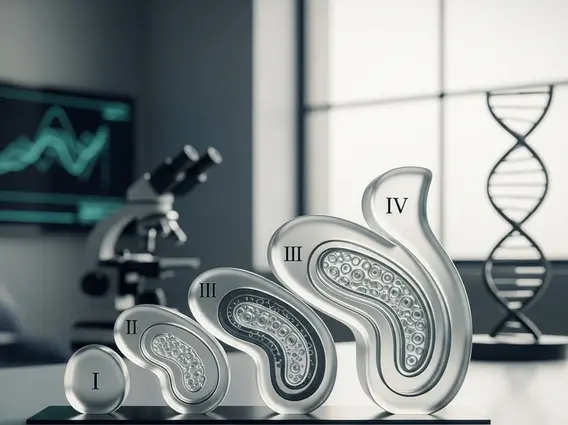

Staging and Classification

Unlike many solid tumors, AML is not typically “staged” using a numerical system (e.g., Stage I, II, III). Instead, it is classified based on the WHO system, which considers the morphology of the leukemia cells, their genetic and molecular characteristics, and the patient’s medical history (e.g., whether it developed from a pre-existing blood disorder or after prior chemotherapy). This detailed classification is essential because it provides critical information about the disease’s aggressiveness, potential response to various treatment options for AML, and overall acute myeloid leukemia prognosis.

Treatment Options and Prognosis for AML

The treatment options for AML are generally aggressive, reflecting the rapid progression of the disease. The choice of therapy depends on several factors, including the patient’s age, overall health, specific AML subtype, and genetic mutations identified during diagnosis.

Current Therapies

The primary goal of AML treatment is to achieve remission by eliminating leukemia cells from the bone marrow and blood.

- Chemotherapy: This is the cornerstone of AML treatment, typically involving two phases:

- Induction chemotherapy: Intensive treatment aimed at killing as many leukemia cells as possible to achieve remission.

- Consolidation chemotherapy: Administered after remission to kill any remaining leukemia cells and prevent relapse.

- Targeted Therapy: These drugs specifically target certain genetic mutations or proteins found in leukemia cells, minimizing harm to healthy cells. Examples include FLT3 inhibitors or IDH inhibitors, used for patients with specific mutations.

- Stem Cell Transplantation (Bone Marrow Transplant): For eligible patients, particularly younger individuals, a stem cell transplant (either allogeneic, from a donor, or autologous, using the patient’s own cells) can be a potentially curative option. It involves high-dose chemotherapy or radiation to destroy the diseased bone marrow, followed by infusion of healthy stem cells.

- Supportive Care: Throughout treatment, supportive care is vital. This includes transfusions of red blood cells and platelets, antibiotics to prevent and treat infections, and medications to manage side effects like nausea and pain.

Managing Life with AML

Living with acute myeloid leukemia presents significant challenges, both physically and emotionally. Patients often endure intensive treatment regimens with substantial side effects, requiring a strong support system and a multidisciplinary care team. This team typically includes oncologists, nurses, social workers, nutritionists, and psychologists, all working to manage symptoms, support mental well-being, and improve quality of life. Long-term follow-up care is essential to monitor for relapse and manage any late effects of treatment.

The acute myeloid leukemia prognosis varies widely. Factors influencing prognosis include the patient’s age (younger patients generally have better outcomes), specific genetic mutations (some are more favorable than others), and how well the disease responds to initial treatment. According to the National Cancer Institute’s SEER program, the overall 5-year relative survival rate for AML is approximately 31.7% (2013-2019 data), but this figure varies significantly by age and other factors. For instance, survival rates are higher for younger patients and those with favorable genetic markers. Continuous research is leading to new therapies and improving outcomes for many patients.

The primary cause of Acute Myeloid Leukemia is the acquisition of genetic mutations in bone marrow stem cells. These mutations disrupt normal cell growth and maturation, leading to the rapid production of abnormal, immature white blood cells. While the exact trigger for these mutations is often unknown, certain risk factors like exposure to specific chemicals (e.g., benzene), previous chemotherapy, or inherited genetic syndromes can increase the likelihood of these mutations occurring.

Treatment for Acute Myeloid Leukemia is generally aggressive and multifaceted. It typically begins with intensive chemotherapy to induce remission, followed by consolidation chemotherapy to prevent relapse. For eligible patients, especially younger individuals, a stem cell transplant may be a curative option. Additionally, targeted therapies are increasingly used for patients with specific genetic mutations, offering more precise treatment with potentially fewer side effects. Supportive care is also crucial throughout the treatment process.

The prognosis for Acute Myeloid Leukemia varies significantly among individuals. It depends on several factors, including the patient’s age, overall health, the specific genetic and molecular characteristics of the leukemia cells, and how well the disease responds to initial treatment. While AML is a serious and rapidly progressing cancer, advancements in treatment, including targeted therapies and improved stem cell transplantation techniques, have led to better outcomes for many patients, particularly those with favorable genetic profiles and who are younger.