Endothelial Cell

Endothelial Cells are fundamental components of the circulatory and lymphatic systems, forming the inner lining of all blood vessels and lymphatic vessels. These specialized cells play a crucial role in maintaining vascular health and regulating various physiological processes throughout the body.

Key Takeaways

- Endothelial Cell refers to the specialized cells that line the interior surface of blood and lymphatic vessels.

- They form a critical barrier, controlling the passage of substances between blood and tissues.

- These cells are diverse in structure and function, adapting to the specific needs of different organs.

- Key functions include regulating blood pressure, inflammation, and blood clotting.

- Dysfunction of Endothelial Cells is implicated in numerous diseases, highlighting their clinical importance.

What is an Endothelial Cell?

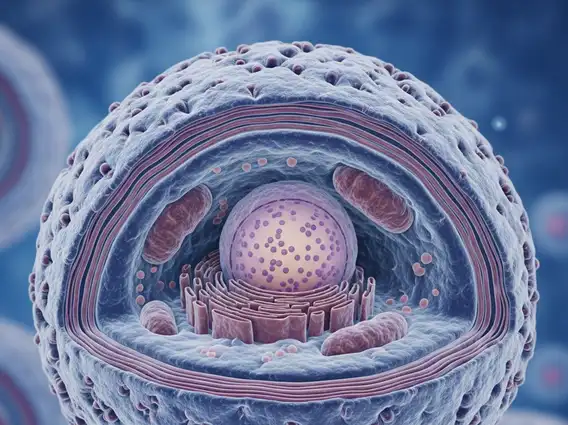

An Endothelial Cell is a type of flattened cell that forms a single layer lining the entire circulatory system, from the heart to the smallest capillaries, as well as the lymphatic vessels. This continuous lining is known as the endothelium. The presence of these cells is ubiquitous; endothelial cells in human body are found in virtually every organ and tissue, forming a vast, intricate network that facilitates nutrient and waste exchange while maintaining vascular integrity.

Functioning as a dynamic interface between the blood and surrounding tissues, Endothelial Cells are far more than just a passive barrier. They actively participate in a wide array of physiological processes, including the regulation of vascular tone, immune responses, and blood coagulation. Their strategic location allows them to sense changes in blood flow and composition, responding by releasing various signaling molecules that influence the behavior of other cells and tissues.

Endothelial Cell Structure and Types

The structure of an Endothelial Cell is typically thin and elongated or polygonal, optimized for forming a smooth, continuous lining. They possess various specialized junctions, such as tight junctions and adherens junctions, which connect adjacent cells and regulate paracellular permeability, ensuring the integrity of the vascular barrier. Internally, these cells contain organelles typical of eukaryotic cells, but also specialized structures like Weibel-Palade bodies, which store and release factors involved in hemostasis and inflammation.

While all Endothelial Cells share core characteristics, their specific endothelial cell structure and types vary significantly depending on their location and the organ they serve. These variations reflect adaptations to local physiological demands:

- Continuous Endothelium: The most common type, found in the brain, muscle, lungs, and skin. These cells form a tight, uninterrupted barrier with minimal permeability, crucial for maintaining the blood-brain barrier.

- Fenestrated Endothelium: Characterized by pores (fenestrae) that allow for rapid exchange of molecules. This type is prevalent in organs involved in filtration and secretion, such as the kidneys (glomeruli), endocrine glands, and intestinal villi.

- Discontinuous (Sinusoidal) Endothelium: Found in organs like the liver, spleen, and bone marrow, these cells have large gaps and an incomplete basement membrane, facilitating the passage of large molecules and even cells between the blood and tissue.

Functions and Clinical Importance of Endothelial Cells

The endothelial cell function and importance are extensive, encompassing critical roles in maintaining homeostasis and responding to pathological challenges. These cells are central to:

- Vascular Tone Regulation: They produce substances like nitric oxide (a potent vasodilator) and endothelin (a vasoconstrictor), thereby controlling blood pressure and blood flow distribution.

- Inflammation and Immunity: Endothelial Cells express adhesion molecules that facilitate the recruitment of immune cells to sites of inflammation or infection.

- Hemostasis and Thrombosis: They maintain a delicate balance between procoagulant and anticoagulant activities, preventing inappropriate blood clot formation while allowing for clotting when necessary.

- Angiogenesis: Endothelial Cells are essential for the formation of new blood vessels, a process vital for wound healing, tissue repair, and embryonic development.

- Selective Permeability: They regulate the passage of nutrients, hormones, and waste products between the blood and surrounding tissues.

The clinical importance of Endothelial Cells cannot be overstated. Dysfunction of the endothelium is a hallmark of numerous diseases, including atherosclerosis, hypertension, diabetes, and sepsis. For instance, endothelial dysfunction is an early event in the development of atherosclerosis, contributing to plaque formation and cardiovascular disease. Understanding the complex roles of these cells is crucial for developing therapeutic strategies aimed at preventing and treating a wide range of human pathologies.