Enchondroma

Enchondroma is a common, benign cartilage tumor that typically develops within the bone marrow. While often asymptomatic, understanding its characteristics is crucial for proper management and patient care.

Key Takeaways

- Enchondromas are non-cancerous cartilage tumors forming inside bones, most commonly in the small bones of the hands and feet.

- They often present without symptoms but can cause pain or fractures if large or located in weight-bearing bones.

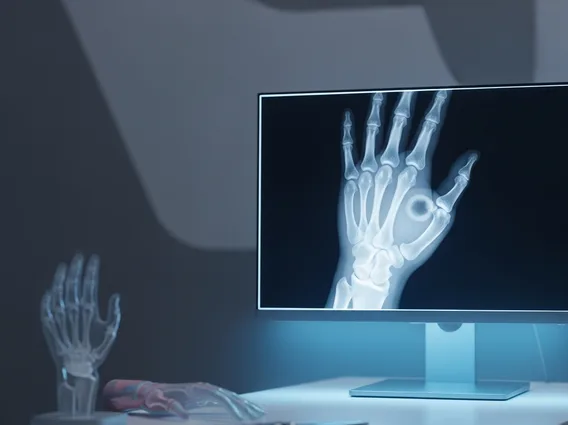

- Diagnosis typically involves imaging tests like X-rays, with biopsy confirming the benign nature when necessary.

- Treatment ranges from watchful waiting for asymptomatic lesions to surgical removal for symptomatic or suspicious cases.

- While generally benign, careful monitoring is important, especially in cases of multiple enchondromas or associated syndromes.

What is Enchondroma?

Enchondroma refers to a type of benign (non-cancerous) bone tumor composed of cartilage tissue that forms within the medullary cavity (the inner part) of a bone. These tumors are among the most common benign bone lesions, frequently affecting the small bones of the hands and feet, though they can also occur in larger long bones like the femur or humerus. They are believed to arise from remnants of growth plate cartilage that become trapped within the bone during development. While solitary enchondromas are most common, multiple enchondromas can indicate specific syndromes, such as Ollier’s disease or Maffucci syndrome, which carry a higher risk of malignant transformation. Providing comprehensive enchondroma bone tumor information is vital for patients to understand this condition, its implications, and the importance of appropriate medical follow-up.

Enchondroma Symptoms and Causes

Most enchondromas are asymptomatic, meaning they do not cause any noticeable symptoms and are often discovered incidentally during X-rays performed for other reasons. However, when symptoms do occur, they typically relate to the tumor’s size, location, or complications.

Common symptoms can include:

- Pain: Usually mild and intermittent, often occurring if the tumor is large, pressing on surrounding structures, or if it weakens the bone, leading to a pathological fracture.

- Swelling or a palpable mass: Especially noticeable in the small bones of the hands and feet.

- Pathological fracture: The weakened bone may break with minimal trauma.

- Deformity: In rare cases, particularly with multiple enchondromas in children, bone growth can be affected, leading to limb deformities.

The exact causes of enchondromas are not fully understood. They are generally considered developmental anomalies, thought to originate from cartilage cells that fail to mature properly and become displaced within the bone. They are not linked to specific lifestyle factors or environmental exposures. Genetic factors are implicated in cases of multiple enchondromas associated with syndromes like Ollier’s disease, characterized by multiple enchondromas, or Maffucci syndrome, which combines multiple enchondromas with soft tissue hemangiomas. These syndromes significantly increase the risk of malignant transformation to chondrosarcoma.

Diagnosing and Treating Enchondroma

The process of enchondroma diagnosis and treatment begins with a thorough clinical evaluation and imaging studies. Initial diagnosis often involves standard X-rays, which typically reveal a well-defined, lytic (bone-destroying) lesion with characteristic calcifications within the bone. Further imaging, such as Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) or Computed Tomography (CT) scans, may be used to assess the tumor’s size, extent, and to differentiate it from other bone lesions, particularly if there is suspicion of malignancy. In some cases, a biopsy may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis and rule out chondrosarcoma, especially if the tumor exhibits aggressive features or causes significant symptoms.

Treatment strategies for enchondroma depend largely on whether the tumor is symptomatic and its potential for malignant transformation.

- Observation: For asymptomatic enchondromas that show no signs of growth or aggressive features on imaging, a “watch and wait” approach is often recommended. Regular follow-up X-rays are typically performed to monitor for any changes.

- Surgical Intervention: Surgery is usually reserved for symptomatic lesions (causing pain or fracture), large tumors, or those with features suggestive of malignancy. The most common surgical procedure is curettage, where the tumor is scraped out of the bone. This cavity is often then filled with bone graft material (either from the patient or a donor) or a bone cement to provide structural support and promote healing. In cases of pathological fracture, surgical stabilization may also be required. The prognosis for solitary enchondromas is excellent after treatment, with a low recurrence rate.