Superior Vena Cava

The superior vena cava is a vital large vein responsible for returning deoxygenated blood from the upper half of the body to the heart. Its proper function is crucial for maintaining healthy circulation.

Key Takeaways

- The Superior Vena Cava (SVC) is a major vein that transports deoxygenated blood from the upper body back to the heart.

- It is formed by the convergence of the left and right brachiocephalic veins and empties into the right atrium.

- The primary superior vena cava function is to ensure efficient venous return from the head, neck, upper limbs, and upper chest.

- Obstruction of the SVC can lead to Superior Vena Cava Syndrome (SVCS), a serious condition often associated with malignancy.

- Common superior vena cava syndrome symptoms include facial and arm swelling, shortness of breath, and distended neck veins.

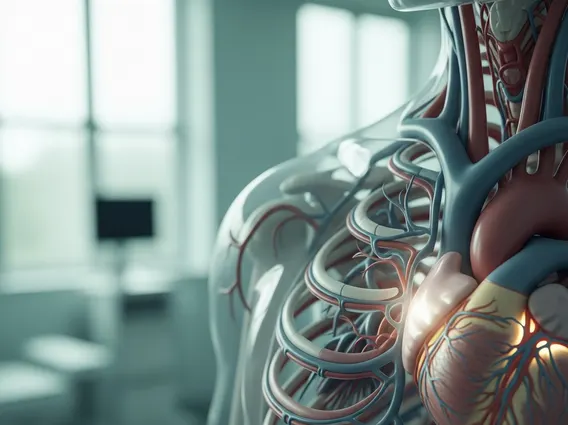

What is the Superior Vena Cava?

The Superior Vena Cava (SVC) is a large, short vein that plays a critical role in the human circulatory system. It is one of the two main venae cavae, responsible for carrying deoxygenated blood from the systemic circulation back to the heart. Specifically, the SVC collects blood from all structures superior to the diaphragm, excluding the heart and lungs themselves, and delivers it directly into the right atrium.

This essential vessel is approximately 7 centimeters long and 2 centimeters in diameter, descending vertically through the upper mediastinum. Its continuous flow ensures that metabolic waste products and carbon dioxide are efficiently removed from the upper body, allowing for oxygenated blood to be supplied through the arterial system.

Superior Vena Cava Anatomy and Function

The superior vena cava anatomy begins behind the lower border of the first right costal cartilage, where the left and right brachiocephalic veins merge. These brachiocephalic veins, in turn, collect blood from the internal jugular veins (draining the head and neck) and the subclavian veins (draining the upper limbs). From its origin, the SVC descends vertically, passing behind the right side of the sternum and eventually piercing the fibrous pericardium at the level of the second costal cartilage. It then terminates by emptying into the superior aspect of the right atrium of the heart, typically at the level of the third costal cartilage.

The primary superior vena cava function is to serve as the main conduit for venous return from the upper body. This includes blood from:

- The head and neck

- Both upper limbs

- The upper chest and parts of the mediastinum

This continuous drainage is vital for maintaining appropriate blood volume and pressure within the cardiovascular system, facilitating the pulmonary circulation where blood is re-oxygenated.

Symptoms of Superior Vena Cava Syndrome

Superior Vena Cava Syndrome (SVCS) is a collection of signs and symptoms that arise when the flow of blood through the superior vena cava is obstructed. This obstruction impairs venous drainage from the head, neck, upper extremities, and upper thorax, leading to increased venous pressure in these regions. SVCS is most commonly associated with malignancy, particularly lung cancer, accounting for up to 80% of cases. (Source: American Cancer Society).

The severity of superior vena cava syndrome symptoms depends on the degree and rapidity of the obstruction, as well as the development of collateral circulation. Common symptoms include:

- Facial swelling (periorbital edema)

- Swelling of the neck and upper extremities

- Shortness of breath (dyspnea)

- Cough

- Chest pain

- Headache and dizziness

- Distended (swollen) veins in the neck and chest wall

- Cyanosis (bluish discoloration) of the face and upper body

In severe cases, cerebral edema (brain swelling) or laryngeal edema (swelling of the voice box) can occur, leading to more critical symptoms such as altered mental status or airway obstruction, which require immediate medical attention.