Osteochondroma

Osteochondroma is the most common type of benign bone tumor, characterized by an overgrowth of cartilage and bone near the growth plate of long bones. This condition typically develops during childhood or adolescence and often stops growing once skeletal maturity is reached.

Key Takeaways

- Osteochondroma is a non-cancerous bone tumor that forms near the ends of long bones.

- Most individuals with osteochondroma experience no symptoms, but it can cause pain, swelling, or nerve compression.

- The exact cause is unknown, but genetic factors, particularly mutations in the EXT1 and EXT2 genes, are linked to its development.

- Diagnosis relies on imaging techniques like X-rays, MRI, or CT scans.

- Treatment often involves observation for asymptomatic cases, with surgical removal considered for symptomatic or problematic lesions.

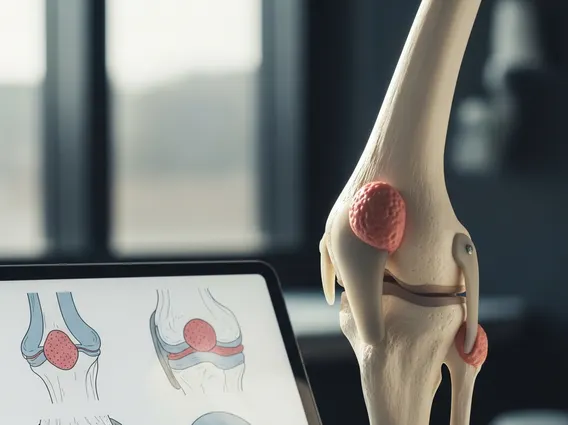

What is Osteochondroma?

Osteochondroma is a benign (non-cancerous) bone tumor that arises from the outer surface of a bone, typically near the growth plates of long bones such as those in the leg, arm, or shoulder blade. It consists of both bone and cartilage, forming a mushroom-shaped or stalk-like projection. This condition is the most frequently encountered benign bone tumor, accounting for approximately 20-50% of all benign bone tumors and 10-15% of all bone tumors overall, according to various orthopedic studies.

An **osteochondroma bone tumor explained** simply is an outgrowth of cartilage-capped bone that develops on the external surface of a bone. While usually solitary, some individuals may develop multiple osteochondromas, a condition known as hereditary multiple exostoses (HME). These tumors usually stop growing once a person reaches skeletal maturity, and the vast majority remain benign, with malignant transformation being a rare occurrence.

Symptoms and Causes of Osteochondroma

Many individuals with osteochondroma are asymptomatic, meaning they experience no noticeable symptoms, and the tumor may only be discovered incidentally during imaging for another condition. However, when symptoms do occur, they can vary depending on the size and location of the growth. Common symptoms include:

- A palpable, painless mass near a joint.

- Pain or soreness if the tumor rubs against surrounding muscles, tendons, or nerves.

- Restricted movement of an adjacent joint.

- Numbness or tingling if the tumor compresses a nerve.

- Weakness in a limb due to nerve compression.

- Changes in limb length or deformity, particularly in cases of hereditary multiple exostoses (HME).

The exact causes of osteochondroma are not fully understood. However, research indicates a strong genetic component, especially for hereditary multiple exostoses (HME). This form is linked to mutations in the EXT1 and EXT2 genes, which are involved in the production of heparan sulfate, a molecule crucial for proper bone growth and development. Solitary osteochondromas are generally sporadic, meaning they occur without a clear family history, though some may also involve mutations in these same genes. The tumors are thought to originate from a displaced piece of growth plate cartilage that continues to grow outside the main bone.

Diagnosing and Treating Osteochondroma

Diagnosing osteochondroma typically begins with a physical examination, where a doctor may feel a hard, fixed mass near a joint. Imaging studies are crucial for confirming the diagnosis and assessing the tumor’s characteristics. These may include:

- X-rays: These are usually the first imaging test, clearly showing the bone outgrowth and its connection to the underlying bone.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): An MRI provides detailed images of the cartilage cap and surrounding soft tissues, helping to evaluate potential nerve or vessel compression and rule out malignancy.

- Computed Tomography (CT) scan: A CT scan can offer more detailed bone architecture, useful for surgical planning.

Treatment for osteochondroma depends largely on whether the tumor is causing symptoms. For asymptomatic osteochondromas, observation is often the recommended approach. Regular monitoring with follow-up X-rays may be advised to track any changes in size or development of symptoms. Surgical removal is considered for tumors that cause pain, restrict joint movement, compress nerves or blood vessels, or if there is concern about malignant transformation (though rare). The surgical procedure involves excising the tumor, including its cartilage cap, to prevent recurrence. The prognosis for individuals with osteochondroma is generally excellent, with most cases resolving without long-term complications after appropriate management.