Nerve Sheath

A nerve sheath is a crucial protective and supportive covering found around nerve fibers throughout the nervous system. These specialized layers are essential for maintaining nerve integrity, facilitating efficient signal transmission, and protecting nerves from damage.

Key Takeaways

- A nerve sheath is a protective layer surrounding nerve fibers, vital for nerve health and function.

- Key anatomical components include the epineurium, perineurium, and endoneurium, each offering distinct levels of protection.

- The primary roles of nerve sheaths involve physical protection, structural support, and insulation for efficient nerve impulse conduction.

- Nerve fibers can be either myelinated or unmyelinated, with myelin sheaths significantly increasing the speed of nerve signal transmission.

- Damage to nerve sheaths can lead to impaired nerve function and various neurological conditions.

What is a Nerve Sheath?

A nerve sheath refers to the protective and supportive connective tissue layers that surround individual nerve fibers and bundles of nerve fibers. These coverings are integral to the structural integrity and functional efficiency of both the central nervous system (CNS) and the peripheral nervous system (PNS). They act as a barrier against physical injury, maintain the internal environment necessary for nerve function, and facilitate the rapid transmission of electrical signals.

The primary role of these sheaths is to safeguard the delicate axons (the long, slender projections of nerve cells that conduct electrical impulses) and to provide a framework that organizes nerve fibers into functional bundles. Without these protective layers, nerves would be highly susceptible to mechanical stress, chemical imbalances, and impaired signal conduction, leading to significant neurological dysfunction.

Nerve Sheath Anatomy and Function

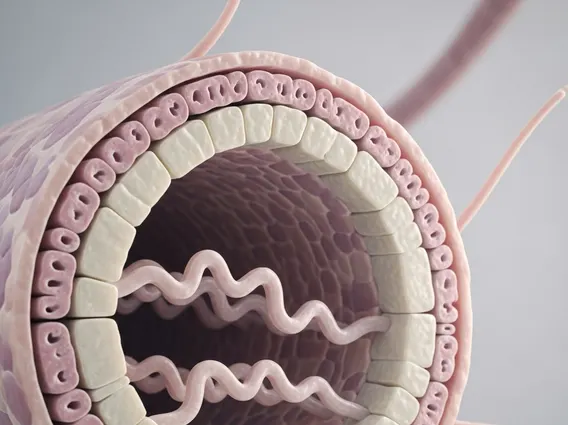

The intricate structure of the nerve sheath is composed of several distinct layers, each contributing to the overall protection and support of nerve fibers. These layers work in concert to ensure the optimal environment for nerve impulse transmission. Understanding the specific roles of these anatomical components is key to appreciating their collective importance.

The main anatomical layers of a peripheral nerve sheath include:

- Epineurium: This is the outermost, thickest layer of connective tissue that surrounds the entire nerve, enclosing multiple fascicles (bundles of nerve fibers). It provides robust mechanical protection and contains blood vessels that supply the nerve.

- Perineurium: This layer surrounds each individual fascicle within the nerve. It forms a strong, protective barrier that maintains the internal environment of the fascicle, regulating the passage of substances and contributing to the blood-nerve barrier.

- Endoneurium: The innermost layer, the endoneurium, surrounds each individual nerve fiber (axon) within a fascicle. It provides a delicate, supportive framework and contains capillaries that supply nutrients directly to the axons.

Beyond structural support, the nerve sheath plays a critical role in nerve impulse conduction. Myelin, a specialized type of nerve sheath, acts as an electrical insulator around many axons. This insulation is crucial for the rapid and efficient propagation of action potentials (nerve impulses) along the nerve fiber. Myelin is formed by Schwann cells in the PNS and oligodendrocytes in the CNS. The presence of myelin allows for saltatory conduction, where the nerve impulse “jumps” between gaps in the myelin sheath called Nodes of Ranvier, significantly increasing transmission speed.

Types of Nerve Sheaths

Nerve fibers are broadly categorized based on the presence or absence of a myelin sheath, leading to two primary types of nerve sheaths: myelinated and unmyelinated. Each type has distinct structural characteristics and functional implications for nerve signal transmission.

Myelinated Nerve Sheaths: These sheaths are characterized by multiple layers of lipid-rich membrane that wrap around the axon, forming a thick insulating layer. In the peripheral nervous system, Schwann cells are responsible for producing myelin, while in the central nervous system, oligodendrocytes perform this function. The primary advantage of myelinated sheaths is their ability to dramatically increase the speed of nerve impulse conduction. This rapid transmission is essential for quick reflexes, motor control, and sensory perception. Damage to these myelin sheaths, as seen in conditions like multiple sclerosis, can severely impair nerve function. Globally, approximately 2.8 million people are affected by multiple sclerosis (MS), a chronic autoimmune disease that damages the myelin sheath of nerves in the brain and spinal cord, according to the Multiple Sclerosis International Federation.

Unmyelinated Nerve Sheaths: In contrast, unmyelinated nerve fibers lack the thick, insulating myelin layers. While Schwann cells in the PNS still envelop multiple unmyelinated axons, they do not form the concentric wraps characteristic of myelin. Nerve impulses in unmyelinated fibers propagate continuously along the axon membrane, a process that is significantly slower than saltatory conduction in myelinated fibers. These fibers are typically involved in functions where speed is less critical, such as certain autonomic responses and the transmission of dull, aching pain.