Colon Crypt

Colon crypts are fundamental microscopic structures within the lining of the large intestine, playing a crucial role in maintaining gut health and function. Understanding their intricate design and cellular activities is essential for comprehending digestive processes and disease mechanisms.

Key Takeaways

- Colon crypts are tubular invaginations in the colon’s lining, housing various specialized cells.

- They are vital for nutrient absorption, water reabsorption, and the secretion of mucus.

- These structures contain stem cells that continuously renew the colonic epithelium.

- The unique anatomy of colon crypts supports their diverse physiological roles.

- Dysfunction in colon crypts can contribute to various gastrointestinal disorders.

What is a Colon Crypt?

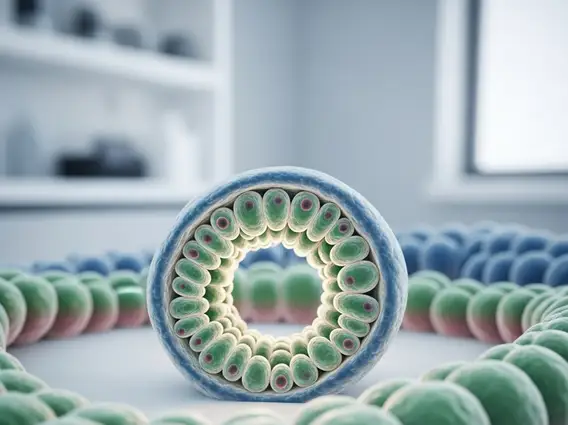

Colon crypts are microscopic, gland-like invaginations found throughout the inner lining, or mucosa, of the large intestine. These tubular structures extend downwards from the surface epithelium into the underlying connective tissue, resembling tiny test tubes or pockets. Each crypt is a highly organized microenvironment, crucial for the colon’s physiological functions. The primary function of these crypts is to facilitate the rapid turnover of epithelial cells, ensuring the integrity and health of the colonic lining. This continuous renewal process is vital for repairing damage and maintaining a robust barrier against harmful substances.

The anatomy of colon crypts reveals a complex cellular arrangement designed for efficiency. At the base of each crypt reside stem cells, which are responsible for generating all the different cell types found along the crypt’s length. As these new cells mature, they migrate upwards towards the luminal surface, differentiating into specialized cells such as absorptive colonocytes, goblet cells, and enteroendocrine cells. This upward migration ensures that old or damaged cells are shed into the intestinal lumen and replaced by fresh, functional cells every few days. This dynamic cellular renewal highlights the critical role of colon crypts in maintaining gut homeostasis.

Colon Crypt Structure and Function

The intricate colon crypt function and structure are central to the large intestine’s role in digestion and overall health. Structurally, each crypt is a single-layered epithelium, but its cellular composition is diverse, allowing for multiple functions. The stem cells at the base are multipotent, meaning they can differentiate into various cell types. Above the stem cells, transit-amplifying cells rapidly divide, expanding the cell population before they begin to differentiate. Further up, mature cells perform specific tasks, contributing to the overall physiological environment of the colon.

Key cell types and their roles within the colon crypts include:

- Colonocytes: These are the most abundant cells, primarily responsible for water and electrolyte absorption from the digested food material, a critical step in forming solid waste. They play a vital role in maintaining the body’s fluid balance.

- Goblet cells: These specialized cells produce and secrete mucin, which forms a protective mucus layer over the epithelial surface. This layer lubricates the passage of stool and shields the underlying cells from mechanical damage, digestive enzymes, and microbial invasion, thus maintaining gut barrier integrity.

- Enteroendocrine cells: Though less numerous, these cells secrete various hormones that regulate digestive processes, such as motility and secretion, in response to luminal contents, influencing overall gut function.

The role of colon crypts in digestion extends beyond simple absorption and protection. They are integral to the gut’s immune defense, acting as a physical barrier and housing immune cells that monitor the intestinal environment for pathogens. The rapid cell turnover also means that the crypts are highly susceptible to damage from inflammation or toxins, making them a key site for the initiation of various colonic diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer. However, this continuous regeneration capacity, driven by the stem cells within these crypts, also provides a robust mechanism for recovery and repair. For instance, the human colon epithelium completely renews itself approximately every 3-5 days, highlighting the dynamic nature and resilience of these essential structures. (Source: National Institutes of Health, NIDDK). This constant renewal is crucial for maintaining a healthy and functional digestive tract.