Transient Myeloproliferative Disorder

Transient Myeloproliferative Disorder (TMD) is a unique and often self-resolving blood condition primarily observed in newborns with Down syndrome. This disorder involves the temporary overproduction of immature blood cells, known as blast cells, in the bone marrow and blood.

Key Takeaways

- Transient Myeloproliferative Disorder (TMD) is a temporary blood disorder predominantly affecting infants with Down syndrome.

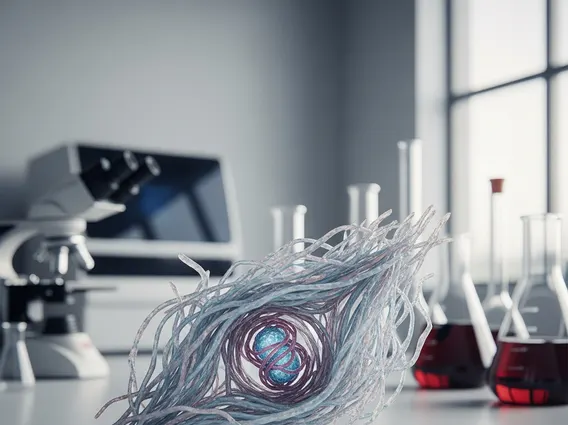

- It is characterized by an abnormal proliferation of immature myeloid cells (blast cells) in the blood and bone marrow.

- TMD is strongly associated with a specific mutation in the GATA1 gene.

- While many cases resolve spontaneously, some infants may require low-dose chemotherapy to manage severe symptoms.

- Infants with TMD have an increased risk of developing myeloid leukemia of Down syndrome (ML-DS) later in childhood, necessitating careful monitoring.

What is Transient Myeloproliferative Disorder (TMD)?

Transient Myeloproliferative Disorder (TMD) is a rare and distinctive hematological condition characterized by the temporary proliferation of immature myeloid cells, or blast cells, in the blood and bone marrow. This disorder almost exclusively affects newborns with Down syndrome (Trisomy 21), with approximately 10% of infants born with Down syndrome developing TMD. It is also sometimes referred to as Transient Leukemia of Down Syndrome. The transient nature of the disorder means that in most cases, the abnormal cell production resolves spontaneously within the first few weeks or months of life without specific intervention.

The underlying cause of TMD is strongly linked to somatic mutations in the GATA1 gene, which plays a critical role in the development of blood cells. These mutations are typically found in the fetal liver and bone marrow cells of affected infants. While the presence of these mutations is key to TMD development, the exact mechanisms that trigger the transient proliferation and subsequent resolution are still areas of ongoing research. Despite its temporary nature, TMD requires careful monitoring due to the potential for severe complications in some infants and an elevated risk of developing acute myeloid leukemia (AML) later in childhood.

Recognizing, Diagnosing, and Managing TMD

Recognizing, diagnosing, and managing Transient Myeloproliferative Disorder involves a multi-faceted approach, beginning with awareness of its characteristic presentation in infants with Down syndrome. The clinical picture can vary significantly, ranging from asymptomatic cases discovered incidentally to severe presentations requiring urgent medical attention.

Recognizing Symptoms and Diagnosis

Transient myeloproliferative disorder symptoms can be diverse. Many infants with TMD are asymptomatic, with the condition only detected through routine blood tests. However, others may present with a range of signs and symptoms, which can include:

- Elevated white blood cell count, particularly immature blast cells.

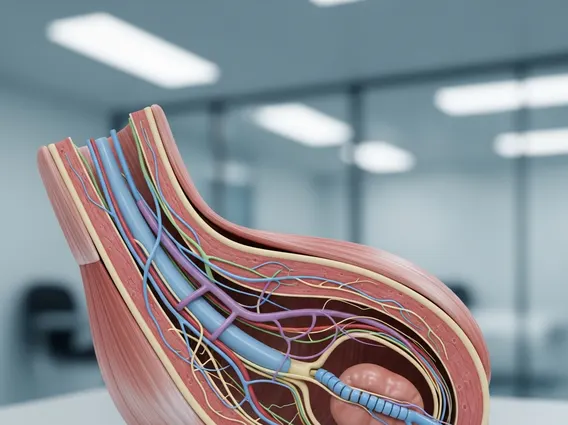

- Hepatomegaly (enlarged liver) or splenomegaly (enlarged spleen).

- Fluid retention (hydrops fetalis or effusions in the chest or abdomen).

- Anemia or thrombocytopenia (low platelet count).

- Skin lesions (leukemia cutis).

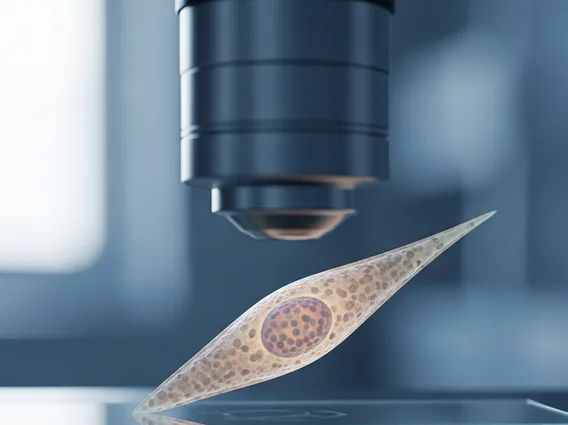

The Transient myeloproliferative disorder diagnosis typically involves a comprehensive evaluation. A complete blood count (CBC) with differential will often reveal an increased number of blast cells in the peripheral blood. A peripheral blood smear examination helps confirm the presence and morphology of these immature cells. Bone marrow examination may be performed to assess the extent of blast infiltration, though it is not always necessary for diagnosis. Crucially, genetic testing for GATA1 mutations is essential to confirm the diagnosis and distinguish TMD from other forms of leukemia, as these mutations are highly characteristic of TMD and subsequent myeloid leukemia of Down syndrome (ML-DS).

Treatment and Monitoring

Transient myeloproliferative disorder treatment strategies are tailored to the severity of the condition. For the majority of infants with TMD, the disorder resolves spontaneously within the first few months of life, and no specific anti-leukemic therapy is required. In these cases, watchful waiting and supportive care are sufficient. However, approximately 10-20% of infants may experience severe symptoms or complications that necessitate intervention. These complications can include significant organ dysfunction, severe anemia, or life-threatening hyperleukocytosis (extremely high blast cell counts).

For infants with severe TMD, low-dose chemotherapy, typically with cytarabine, may be administered to reduce the blast cell burden and manage symptoms. The goal of treatment is to control the disease and prevent complications while minimizing toxicity, given the transient nature of the disorder. Long-term follow-up is critical for all infants diagnosed with TMD, even those whose condition resolved spontaneously. This is because approximately 20-30% of children with a history of TMD will later develop myeloid leukemia of Down syndrome (ML-DS) within the first four years of life. Regular monitoring, including blood counts and clinical assessments, is essential to detect any signs of leukemia recurrence or progression early, allowing for timely intervention.