Poly Adp Ribose Polymerase

Poly Adp Ribose Polymerase (PARP) is a crucial family of enzymes involved in various cellular processes, most notably DNA repair. Understanding its function is vital for comprehending cellular integrity and the development of certain medical therapies.

Key Takeaways

- Poly Adp Ribose Polymerase (PARP) is a family of enzymes essential for maintaining genomic stability.

- PARP primarily functions in detecting and repairing DNA damage, particularly single-strand breaks.

- The enzyme catalyzes the addition of ADP-ribose units to target proteins, forming poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) chains.

- This PARylation process recruits other repair proteins to the site of DNA damage.

- PARP’s role in DNA repair makes it a significant target in oncology, especially for enhancing the efficacy of chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

What is Poly Adp Ribose Polymerase (PARP)?

Poly Adp Ribose Polymerase (PARP) refers to a family of enzymes found in the nucleus of eukaryotic cells, playing a pivotal role in maintaining genomic integrity. These enzymes are primarily known for their involvement in DNA repair, but they also participate in other cellular processes such as transcription, cell death, and inflammation. The most well-studied member of this family is PARP-1, which accounts for over 90% of cellular PARP activity and is highly abundant in the cell nucleus.

PARP enzymes detect and bind to DNA breaks, acting as immediate responders to cellular stress. Upon binding, they initiate a complex signaling cascade that ultimately leads to the repair of damaged DNA. This rapid response is critical for preventing mutations, maintaining genetic stability, and ensuring proper cell function. Dysregulation of PARP activity can lead to genomic instability, which is a hallmark of various diseases, including cancer.

Role of PARP in DNA Repair and Cellular Processes

The primary Poly Adp Ribose Polymerase function is its critical involvement in DNA repair pathways, particularly the base excision repair (BER) pathway. This pathway is responsible for repairing single-strand breaks (SSBs) in DNA, which are common forms of DNA damage caused by metabolic byproducts, environmental factors, and radiation. When a single-strand break occurs, PARP-1 rapidly detects the lesion and binds to the site.

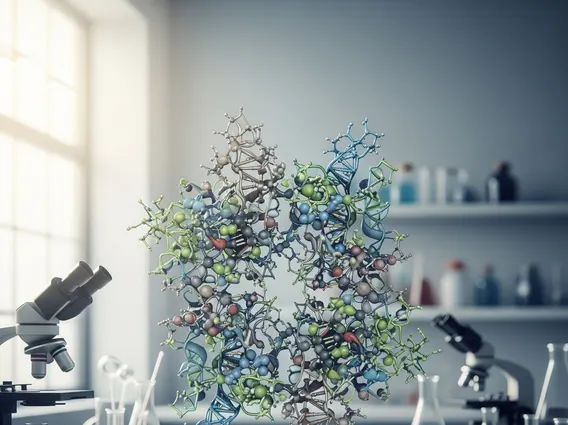

Once bound, PARP-1 undergoes a conformational change that activates its catalytic domain. This activation initiates a process called PARylation, where PARP synthesizes long, branched chains of poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) from NAD+ molecules and attaches them to various acceptor proteins, including itself and histones. These PAR chains serve as a signal, creating a scaffold that recruits other DNA repair proteins to the site of damage. This coordinated recruitment ensures efficient and timely repair, preventing the accumulation of harmful DNA lesions. The Role of PARP in DNA repair is thus central to cellular survival and genomic stability.

Beyond single-strand break repair, PARP also contributes to other cellular processes:

- Transcription Regulation: PARP can influence gene expression by modifying chromatin structure.

- Apoptosis (Programmed Cell Death): While excessive PARP activation can lead to a form of cell death called parthanatos, controlled PARP activity is also involved in the initiation of apoptosis.

- Chromatin Remodeling: PARP’s PARylation of histones can alter chromatin accessibility, affecting DNA-dependent processes.

- Inflammation: PARP has been implicated in inflammatory responses, modulating the activity of immune cells.

Mechanism of Poly Adp Ribose Polymerase Action

The Poly Adp Ribose Polymerase mechanism of action involves a sophisticated enzymatic process. Upon detecting a DNA single-strand break, PARP-1 rapidly binds to the DNA lesion through its N-terminal DNA-binding domain. This binding event triggers an allosteric activation of the enzyme’s catalytic domain, located at the C-terminus.

The activated catalytic domain then utilizes nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) as a substrate. PARP-1 cleaves NAD+ into nicotinamide and ADP-ribose. It then catalyzes the transfer of the ADP-ribose moiety to specific acceptor proteins, forming a covalent bond. This process is repeated multiple times, leading to the synthesis of long, often branched, chains of poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR). These PAR chains can be attached to PARP itself (auto-PARylation) or to other nuclear proteins, including histones and DNA repair factors.

The negatively charged PAR chains act as a molecular signal, facilitating the recruitment of various DNA repair proteins, such as XRCC1 and DNA ligase III, to the site of damage. This localized concentration of repair factors accelerates the repair process. Once the DNA damage is repaired, the PAR chains are rapidly degraded by poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase (PARG), allowing the cellular machinery to return to its basal state. This dynamic PARylation and de-PARylation cycle is crucial for the precise regulation of DNA repair and other PARP-mediated cellular functions.