Pathologic Fracture

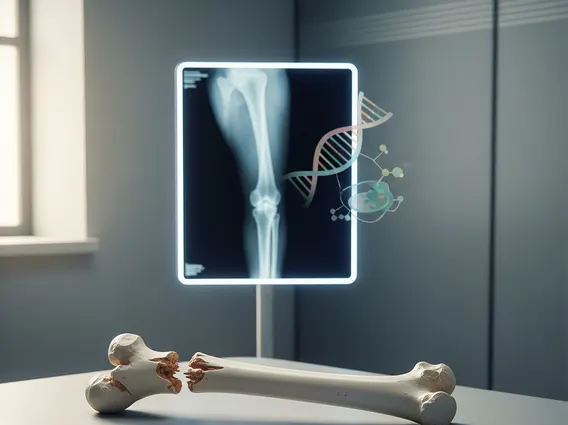

A pathologic fracture is a bone break that occurs because an underlying disease has weakened the bone, rather than from significant trauma or injury. These fractures are a serious complication of various medical conditions, often indicating compromised bone integrity.

Key Takeaways

- A pathologic fracture results from weakened bone due to disease, not typical injury.

- Common causes include metastatic cancer, primary bone tumors, osteoporosis, and infections.

- Symptoms often include sudden pain, swelling, and difficulty with movement, sometimes preceded by persistent bone pain.

- Diagnosis involves imaging (X-rays, CT, MRI) and often a biopsy to identify the underlying cause.

- Treatment addresses both the fracture stabilization and the underlying disease, influencing the overall prognosis.

What is a Pathologic Fracture?

A pathologic fracture refers to a bone fracture that occurs spontaneously or with minimal trauma due to a pre-existing disease that has weakened the bone structure. Unlike traumatic fractures, which result from significant force, these breaks happen because the bone’s normal strength and integrity have been compromised. Understanding what is a pathologic fracture? is crucial for appropriate diagnosis and management, as it signals an underlying health issue that requires attention beyond just mending the broken bone.

The bone’s structural weakness can stem from various conditions, making it susceptible to breaks under stresses that a healthy bone would easily withstand. This can range from daily activities like walking or turning in bed to minor falls that would typically only cause a bruise. The presence of such a fracture often serves as an initial indicator of an undiagnosed systemic illness or a progression of a known disease.

Causes, Symptoms, and Diagnosis

The underlying conditions that lead to pathologic fractures are diverse, primarily involving processes that erode or replace healthy bone tissue. The most common causes are cancers that have spread to the bone (metastatic cancer), primary bone tumors, severe osteoporosis, and certain infections. For instance, bone metastases are a significant concern, affecting approximately 30-70% of patients with advanced cancers such as breast, prostate, and lung cancer, according to the American Cancer Society, making them a leading cause of bone weakening and subsequent fractures.

Pathologic fracture causes and symptoms can vary depending on the specific underlying condition and the location of the fracture. Common symptoms include sudden, severe pain at the fracture site, which may be disproportionate to any perceived injury. Other signs can include swelling, bruising, and noticeable deformity of the affected limb. Often, patients may experience persistent, dull bone pain for weeks or months before the actual fracture occurs, indicating progressive bone weakening.

How are pathologic fractures diagnosed? The diagnostic process typically begins with a thorough medical history and physical examination, especially inquiring about any history of cancer or other chronic diseases. Imaging studies are essential for confirming the fracture and identifying the underlying bone lesion. These may include:

- X-rays: Initial imaging to identify the fracture and visible bone lesions.

- Computed Tomography (CT) scans: Provide detailed cross-sectional images of the bone and surrounding tissues.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Offers excellent soft tissue contrast, useful for evaluating bone marrow and tumor extent.

- Bone scans (scintigraphy): Can detect increased bone turnover associated with tumors or infections throughout the skeleton.

- Biopsy: A sample of the bone lesion is often taken to determine the exact nature of the underlying disease, especially in cases of suspected cancer.

Treatment and Outlook

Pathologic fracture treatment and prognosis are highly individualized, depending significantly on the underlying cause, the patient’s overall health, and the fracture’s location and severity. The primary goals of treatment are to stabilize the fracture, alleviate pain, restore function, and most importantly, address the disease that weakened the bone. For immediate fracture management, surgical intervention is often necessary to stabilize the bone, using methods such as internal fixation (rods, plates, screws) or external fixation. In some cases, casting or bracing may be sufficient.

Concurrently, treatment for the underlying condition is initiated or intensified. This might involve chemotherapy, radiation therapy, hormone therapy, or targeted drug therapies for cancer. For osteoporosis, medications to improve bone density are prescribed. Infections require appropriate antibiotic or antifungal treatments. Rehabilitation, including physical and occupational therapy, is crucial post-treatment to help patients regain strength, mobility, and independence.

The prognosis for individuals with pathologic fractures varies widely. For those with benign conditions like severe osteoporosis, the outlook for fracture healing and functional recovery can be good with appropriate management. However, when the fracture is due to advanced metastatic cancer, the prognosis is often more guarded, focusing on pain control, maintaining quality of life, and preventing further complications. Early diagnosis and a multidisciplinary approach involving orthopedic surgeons, oncologists, radiologists, and rehabilitation specialists are vital for optimizing outcomes and improving the patient’s long-term outlook.