Nerve Block

A Nerve Block is a medical procedure designed to manage pain by temporarily interrupting nerve signals. This intervention is often used for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes, offering relief for various acute and chronic pain conditions.

Key Takeaways

- Nerve blocks temporarily stop pain signals from reaching the brain.

- They involve injecting an anesthetic or other medication near specific nerves.

- Common types include epidural, spinal, and peripheral nerve blocks.

- The procedure is typically quick, performed under local anesthesia, and may involve imaging guidance.

- Nerve blocks are used for pain management, surgical anesthesia, and diagnostic purposes.

What is a Nerve Block?

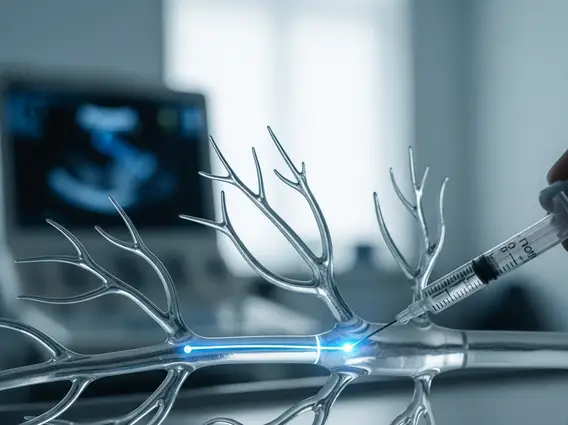

A nerve block refers to a medical procedure involving the injection of an anesthetic or other medication directly onto or near nerves to temporarily interrupt pain signals. This intervention aims to alleviate pain, reduce inflammation, or provide anesthesia for surgical procedures. By blocking the transmission of nerve impulses, a nerve block can offer significant relief from various types of pain, ranging from acute post-surgical discomfort to chronic conditions like sciatica or complex regional pain syndrome. The primary goal is to target specific nerves responsible for transmitting pain sensations to the brain, thereby providing localized and effective pain control.

How Nerve Blocks Work and Their Types

Nerve blocks work by delivering a substance, typically a local anesthetic, to a specific nerve or group of nerves. This anesthetic temporarily numbs the nerves, preventing them from sending pain signals to the brain. In some cases, other medications like steroids are included to reduce inflammation and provide longer-lasting pain relief. The effect is localized, meaning only the targeted area loses sensation or pain transmission, while other parts of the body remain unaffected. The duration of relief varies depending on the type of medication used and the individual’s response.

There are several types of nerve blocks and uses, each tailored to target different areas of the body and specific pain conditions:

- Epidural Block: Involves injecting medication into the epidural space surrounding the spinal cord, commonly used for labor pain, back pain, and certain surgeries.

- Spinal Block: Medication is injected directly into the cerebrospinal fluid within the spinal canal, providing rapid and profound anesthesia, often for lower body surgeries.

- Peripheral Nerve Block: Targets individual nerves or nerve plexuses outside the spinal cord, used for pain in limbs, hands, or feet, and as anesthesia for localized surgeries.

- Sympathetic Nerve Block: Aims to block nerves in the sympathetic nervous system, often used for pain caused by conditions like complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) or certain vascular issues.

- Facet Joint Block: Targets the small joints between the vertebrae in the spine, used to diagnose and treat back and neck pain originating from these joints.

The Nerve Block Procedure

The nerve block procedure explanation typically involves several steps, ensuring patient safety and optimal outcomes. Before the procedure, a healthcare provider will review the patient’s medical history, current medications, and conduct a physical examination to determine the most appropriate type of block. Patients may be asked to fast for a few hours prior to the procedure.

During the procedure, the patient is usually positioned comfortably, and the skin over the injection site is cleaned with an antiseptic solution. A local anesthetic is often applied to numb the skin, minimizing discomfort from the needle insertion. The healthcare provider then carefully inserts a thin needle, often guided by imaging techniques such as fluoroscopy (real-time X-ray) or ultrasound. These imaging tools allow the provider to visualize the nerves and surrounding structures, ensuring precise placement of the needle and medication. Once the needle is in the correct position, the anesthetic or other therapeutic medication is slowly injected. Patients might feel a brief pressure or tingling sensation during the injection. After the injection, the needle is removed, and a small bandage is applied. Patients are typically monitored for a short period to ensure there are no immediate adverse reactions before being discharged. Recovery time varies, but most individuals can resume light activities within a day or two, following specific post-procedure instructions.