Breast Lobe

The human breast is a complex organ vital for lactation, composed of various tissues including glandular, fatty, and connective tissues. Central to its function are structures known as breast lobes, which play a crucial role in milk production and overall breast health.

Key Takeaways

- Breast lobes are the primary glandular units within the breast responsible for milk production.

- Each breast typically contains 15 to 20 lobes, arranged radially around the nipple.

- Lobes are further divided into smaller lobules, which contain alveoli where milk is synthesized.

- A network of ducts connects the lobules within the lobes to the nipple, transporting milk out of the breast.

- Understanding breast lobe anatomy is essential for comprehending breast health and the origin of many common breast conditions.

What is a Breast Lobe?

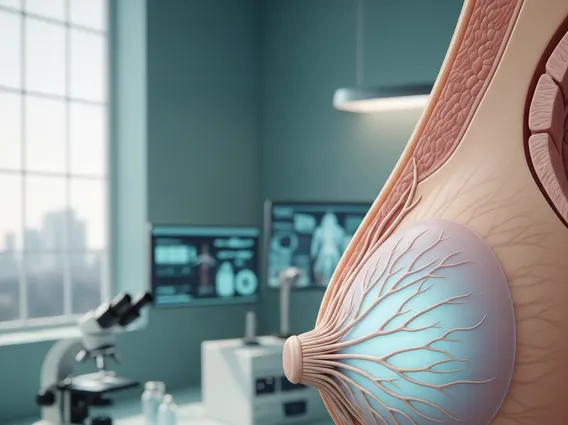

A breast lobe is a major glandular segment within the breast, serving as the fundamental unit for milk production. To understand what is a breast lobe, it’s important to recognize it as a collection of smaller glands called lobules, all draining into a common lactiferous duct. These lobes are embedded within fatty and connective tissues, which give the breast its shape and support. Their primary function is to produce and transport milk during lactation, a process initiated by hormonal signals during pregnancy and childbirth. Each lobe acts as an independent unit, contributing to the overall milk-producing capacity of the breast. Beyond lactation, the health and integrity of these lobes are crucial for overall breast well-being, as many common breast conditions, both benign and malignant, originate within these glandular structures.

Breast Lobe Anatomy, Function, and Number

The intricate breast lobe function and anatomy are central to the breast’s role in lactation and overall health. Typically, each human breast contains between 15 to 20 distinct lobes, though this number can vary slightly among individuals. These lobes are arranged in a radial pattern, much like the spokes of a wheel, converging towards the nipple. This arrangement allows for efficient collection and transport of milk from various parts of the breast, ensuring that milk can be effectively delivered during breastfeeding.

Within each lobe, the internal breast lobe structure explained involves a hierarchy of smaller units. Each lobe is subdivided into numerous smaller structures called lobules. These lobules are the microscopic sites of milk production, containing clusters of specialized milk-secreting cells known as alveoli. During pregnancy and in response to hormones like prolactin, these alveoli proliferate and mature significantly, preparing for the synthesis and secretion of breast milk. The surrounding stromal tissue, composed of connective tissue and fat, provides essential support and houses blood vessels and nerves vital for the lobules’ function, ensuring a rich supply of nutrients and hormonal signals.

The milk produced in the alveoli travels through tiny ducts within the lobules, which then merge into larger ducts. These larger ducts, known as lactiferous ducts, emerge from each lobe and converge towards the nipple, where they widen slightly into lactiferous sinuses before opening onto the surface. This extensive network of ducts ensures efficient transport of milk out of the breast during breastfeeding. The fatty tissue surrounding the lobes and ducts provides protection, insulation, and contributes significantly to breast size and shape, while fibrous connective tissue offers crucial structural support, anchoring the glandular components and maintaining breast integrity. Understanding how many lobes in a breast and their detailed structure is fundamental, as these areas are often the origin points for various breast conditions, including benign changes like cysts and fibroadenomas, as well as malignant conditions. For instance, ductal and lobular carcinomas are named precisely for the specific glandular structures from which they arise, highlighting the clinical significance of this anatomy in diagnostics and treatment. (Source: National Cancer Institute, general anatomical descriptions and pathology classifications).