Photosensitizer

A photosensitizer is a specialized chemical compound that becomes reactive upon exposure to light of a specific wavelength, initiating a photochemical process. These compounds are integral to various medical treatments, particularly in oncology and ophthalmology, due to their ability to selectively target and destroy diseased cells.

Key Takeaways

- A photosensitizer is a light-sensitive compound that, when activated by specific light wavelengths, produces reactive oxygen species.

- These compounds are primarily utilized in photodynamic therapy (PDT) for their ability to selectively damage target cells.

- PDT, leveraging photosensitizers, is a minimally invasive treatment option for various cancers and non-cancerous conditions.

- Different generations and types of photosensitizers exist, each optimized for particular clinical applications and light penetration depths.

What is a Photosensitizer?

A photosensitizer is a substance that absorbs light energy and then transfers this energy to other molecules, typically oxygen, to produce highly reactive chemical species. In a medical context, these compounds are designed to be relatively inert until activated by light. Once illuminated with light of a specific wavelength, the photosensitizer undergoes a transformation, leading to a localized therapeutic effect. This targeted activation minimizes damage to healthy surrounding tissues, making them valuable tools in precision medicine.

The concept behind these agents relies on their unique photophysical and photochemical properties. They are often administered systemically or topically and are designed to accumulate preferentially in target cells, such as cancerous cells. This selective uptake, combined with precise light delivery, allows for highly localized treatment.

Mechanism of Action and Types of Photosensitizers

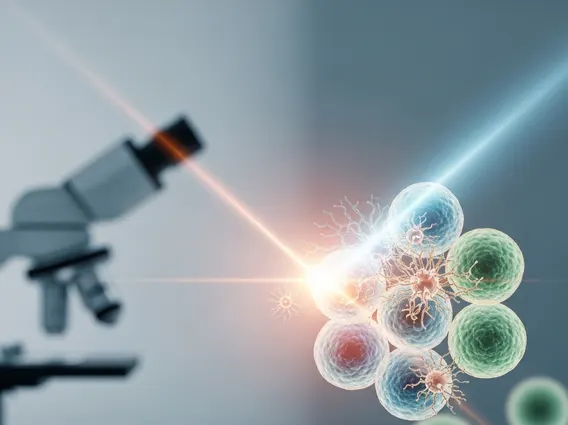

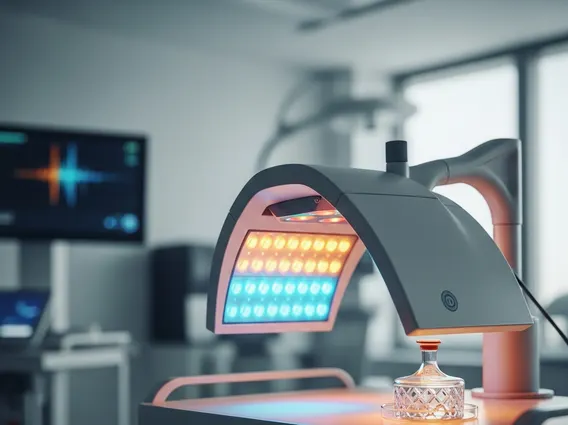

The core principle of how photosensitizers work involves a series of photochemical reactions. Upon absorbing photons from a specific light source (often a laser or LED), the photosensitizer molecule transitions from its ground state to an excited singlet state. It then rapidly converts to a longer-lived excited triplet state. From this triplet state, the photosensitizer can interact with molecular oxygen present in the tissue. This interaction typically results in the generation of highly reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as singlet oxygen (1O2) and superoxide radicals.

These ROS are potent cytotoxic agents that can damage various cellular components, including lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, ultimately leading to cell death through apoptosis or necrosis. The efficacy of the treatment depends on several factors, including the photosensitizer’s concentration in the target tissue, the wavelength and dose of light, and the oxygen availability within the tissue.

There are several types of photosensitizers, often categorized by their chemical structure and generation:

- First-Generation Photosensitizers: These include hematoporphyrin derivatives, such as Photofrin. While effective, they often cause prolonged skin photosensitivity.

- Second-Generation Photosensitizers: Developed to improve upon the first generation, these compounds offer better light absorption at longer wavelengths (allowing deeper tissue penetration), reduced systemic photosensitivity, and higher singlet oxygen yields. Examples include aminolevulinic acid (ALA) and its esters (which lead to endogenous protoporphyrin IX production), phthalocyanines, and chlorins.

- Third-Generation Photosensitizers: These are still largely in experimental stages and aim for even greater tumor selectivity and improved pharmacokinetic profiles, often through conjugation with targeting moieties.

Medical Uses of Photosensitizers

The primary application of photosensitizer medical uses is in photodynamic therapy (PDT). PDT is a minimally invasive treatment that combines a photosensitizer, light, and oxygen to destroy abnormal cells. It has gained significant recognition for its effectiveness in treating a variety of medical conditions, particularly in oncology and ophthalmology.

In oncology, PDT is approved for treating several types of cancer, including certain non-small cell lung cancers, esophageal cancer, bladder cancer, and specific skin cancers such as basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma in situ. The localized nature of PDT allows for precise targeting of tumors while sparing surrounding healthy tissue, which can lead to better cosmetic and functional outcomes, especially for superficial lesions. For instance, the American Cancer Society notes PDT as an option for certain cancers, highlighting its role in targeted cancer treatment strategies.

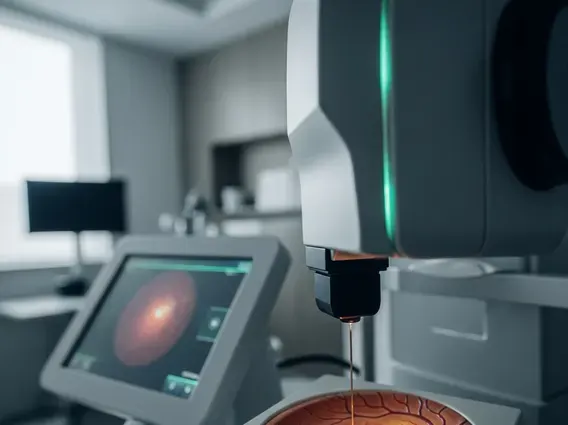

Beyond cancer, photosensitizers are also used in treating non-oncological conditions. A notable application is in ophthalmology for age-related macular degeneration (AMD), where PDT helps to close abnormal blood vessels that contribute to vision loss. It is also used for conditions like actinic keratosis, a common precancerous skin lesion, and certain infectious diseases, leveraging the broad cytotoxic effects of the generated reactive oxygen species.