Optic Pathway Glioma

Optic Pathway Glioma is a rare type of brain tumor that affects the visual system, primarily occurring in children. Understanding this condition is crucial for early diagnosis and effective management.

Key Takeaways

- Optic Pathway Glioma is a slow-growing tumor affecting the optic nerves, chiasm, or tracts, most common in children.

- Symptoms often include vision changes, involuntary eye movements, and hormonal imbalances, necessitating careful observation.

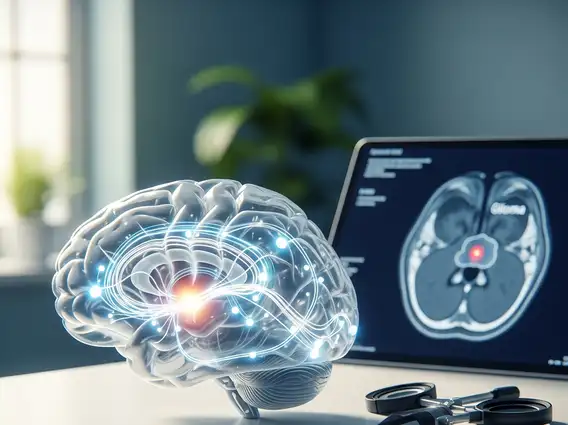

- Diagnosis typically involves neuroimaging (MRI) and ophthalmological examinations.

- Treatment approaches vary based on tumor location, size, and patient age, ranging from observation to chemotherapy or surgery.

- Genetic conditions like Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) are frequently associated with its development.

What is Optic Pathway Glioma?

Optic Pathway Glioma (OPG) refers to a slow-growing, low-grade tumor that originates in the optic nerves, optic chiasm, or optic tracts. These structures are vital components of the visual pathway, responsible for transmitting visual information from the eyes to the brain. While OPGs can occur at any age, they are most commonly diagnosed in children, particularly those under the age of 10. These tumors are often benign (non-cancerous) but can still cause significant problems due to their critical location, potentially leading to vision loss and other neurological or endocrine issues.

The exact causes of Optic Pathway Glioma are not fully understood, but a significant number of cases are associated with Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), a genetic disorder. Approximately 15-20% of individuals with NF1 develop OPGs, making it the most common central nervous system tumor in this population. For those without NF1, the cause is often sporadic and unknown. According to the National Cancer Institute, gliomas are the most common type of primary brain tumor, and OPGs represent a specific subtype within this category, highlighting their prevalence within pediatric neuro-oncology.

Recognizing Optic Pathway Glioma Symptoms

The optic pathway glioma symptoms can vary widely depending on the tumor’s size, exact location within the visual pathway, and the child’s age. Because the tumor affects vision, changes in eyesight are often among the first indicators. However, symptoms can be subtle and progress slowly, making early detection challenging, especially in very young children who cannot articulate their visual difficulties.

Common signs and symptoms to look for include:

- Vision Loss: This can range from mild blurring to complete blindness in one or both eyes. Parents might notice a child bumping into objects or struggling with tasks requiring good vision.

- Proptosis (Bulging Eye): If the tumor is located within the optic nerve behind the eye, it can push the eyeball forward.

- Nystagmus: Involuntary, rapid eye movements, which may be a sign of impaired vision or neurological involvement.

- Strabismus (Crossed Eyes): Misalignment of the eyes can occur due to visual impairment or nerve compression.

- Endocrine Dysfunction: Tumors affecting the optic chiasm, which is close to the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, can interfere with hormone production, leading to issues like precocious puberty, growth hormone deficiency, or diabetes insipidus.

- Headaches and Nausea: Less common, but can occur if the tumor grows large enough to increase intracranial pressure.

Regular ophthalmological examinations are crucial for children at risk, particularly those with NF1, to monitor for any subtle changes that might indicate the presence of an OPG.

Optic Pathway Glioma Treatment Options

The optic pathway glioma treatment options are highly individualized, taking into account several factors such as the child’s age, the tumor’s size and location, the extent of vision loss, and the presence of NF1. The primary goal of treatment is to preserve vision and prevent tumor progression while minimizing long-term side effects.

Treatment strategies often include:

- Observation: For small, asymptomatic tumors or those not causing significant vision loss, a “watch and wait” approach with regular MRI scans and ophthalmological evaluations may be adopted. This avoids unnecessary treatment side effects if the tumor remains stable.

- Chemotherapy: This is often the first-line treatment for progressive OPGs, especially in young children, to shrink the tumor and stabilize vision. Chemotherapy regimens are typically low-dose and administered over an extended period to minimize toxicity.

- Radiation Therapy: While effective in controlling tumor growth, radiation therapy is generally reserved for older children or cases where chemotherapy has failed, due to the potential for long-term neurocognitive and endocrine side effects in young, developing brains.

- Surgery: Surgical removal of OPGs is challenging and often not feasible without causing further vision loss, given the delicate nature of the optic pathway. It may be considered in specific cases, such as for tumors causing severe proptosis or when a biopsy is needed for diagnosis.

A multidisciplinary team, including neuro-oncologists, ophthalmologists, neurosurgeons, and endocrinologists, typically collaborates to determine the most appropriate course of action, ensuring comprehensive care for each patient.