Cold Ischemia Time

Cold Ischemia Time is a critical factor in organ transplantation, referring to the period an organ is preserved outside the body under cold conditions before implantation. Understanding and minimizing this duration is vital for successful transplant outcomes.

Key Takeaways

- Cold Ischemia Time (CIT) is the interval an organ spends in a cold, non-perfused state between removal from the donor and reperfusion in the recipient.

- Minimizing CIT is crucial for preserving organ viability and function post-transplantation.

- Prolonged CIT can lead to cellular damage, increased risk of complications, and reduced long-term graft survival.

- Different organs have varying tolerances to CIT, with some being more sensitive than others.

- Effective organ preservation techniques and efficient logistical coordination are essential to reduce CIT.

What is Cold Ischemia Time?

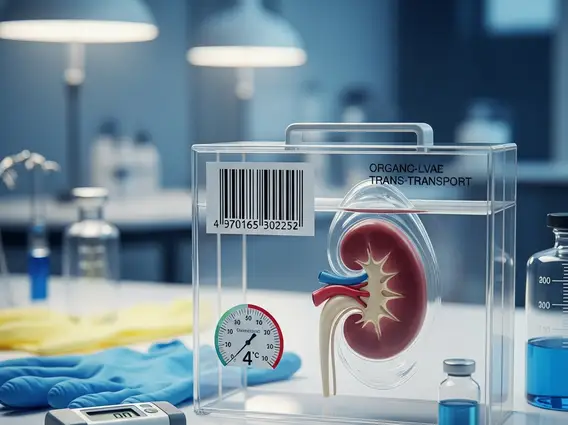

Cold Ischemia Time (CIT) refers to the period during which an organ is kept in a hypothermic, non-perfused state after its removal from the donor and prior to its revascularization in the recipient. This process is fundamental in organ transplantation, as it slows down the metabolic rate of cells, thereby reducing their oxygen and nutrient demands. The primary goal of cold preservation is to minimize cellular injury and maintain organ viability during transport and storage.

The cold ischemia time definition encompasses the entire duration from the clamping of the blood vessels in the donor to the restoration of blood flow in the recipient. During this period, organs are typically flushed with and stored in specialized preservation solutions at temperatures between 0-8°C. These solutions are designed to protect cells from damage by providing necessary electrolytes, buffers, and osmotic agents, while the cold temperature significantly reduces cellular metabolism and the accumulation of harmful byproducts.

Cold Ischemia Time in Organ Transplantation

The significance of cold ischemia time in transplantation cannot be overstated, as it directly impacts the success and longevity of the transplanted organ. While cold preservation extends the window for transplantation, every minute counts. The acceptable duration of CIT varies significantly depending on the type of organ due to differences in cellular composition and metabolic rates. For instance, kidneys generally tolerate longer cold ischemia periods than hearts or lungs.

Efficient logistical coordination, including rapid donor-recipient matching, swift organ recovery, and expedited transport, is paramount to minimizing CIT. Transplant teams work rigorously to ensure that organs are transplanted as quickly as possible to preserve their function. Prolonged CIT can lead to increased rates of delayed graft function, acute rejection, and reduced long-term graft survival, underscoring the importance of meticulous planning and execution in the transplant process.

The following table illustrates typical cold ischemia time limits for various organs:

| Organ | Typical Cold Ischemia Time Limit |

|---|---|

| Heart | 4-6 hours |

| Lung | 4-8 hours |

| Liver | 8-12 hours |

| Pancreas | 12-18 hours |

| Kidney | 24-36 hours |

Effects of Cold Ischemia Time on Organ Viability

The effects of cold ischemia time on organ viability are profound and multifaceted. Although hypothermia protects organs by reducing metabolic demand, prolonged periods without blood flow can still lead to significant cellular injury. This damage often manifests as ischemia-reperfusion injury, a complex process that occurs when blood flow is restored to ischemic tissues. During ischemia, cells accumulate waste products and undergo structural changes. Upon reperfusion, the sudden influx of oxygen and inflammatory mediators can trigger a cascade of events, including oxidative stress, inflammation, and cell death.

Studies have consistently shown a correlation between extended CIT and adverse outcomes. For example, a study published in the American Journal of Transplantation highlighted that longer cold ischemia times in kidney transplantation are associated with a higher incidence of delayed graft function and a greater risk of chronic allograft nephropathy. Similarly, in liver transplantation, prolonged CIT can increase the risk of primary non-function and biliary complications. Minimizing CIT is therefore a critical strategy to mitigate these risks, improve initial graft function, and enhance the long-term survival of transplanted organs and recipients.